Orellana's arrabel

Note 002

Home > Blog A Musician's Log > Note 002

One of the problems of historical, anthropological and ethnographic sources when providing organological information is that authors are generally neither familiar with the musical universe nor with the specific terminology to identify it. Thus, it is not strange to find, in old (and not so old) bibliographic sources, flutes called trumpets, trumpets called clarinets, clarinets called flutes, and the use of an ambiguous vocabulary, including terms such as "caramillos" or "gaitas" (particularly in old Spanish colonial texts, which many times are the basis of my work.)

This ambiguity found in the labels chosen by authors of the distant and recent past to name the sound artifacts they were trying to describe derives from one of the characteristics of human classification systems. These systems, inherent to any individual, are based on the comparison of what is observed —of what one wants to understand, name and/or classify— with elements already known from one's own cultural heritage, which corresponds to a specific territory, time, and group. Thus, a 16th-century Andalusian, Extremaduran orManchegan would call "gaita" any narrow idioglottic clarinet, or even some types of flutes, but an Aragonese or a Galician would use the term for something else. A 19th-century Swede from an urban environment would speak of timpani, bassoons and cellos to refer to indigenous instruments, especially if he had had no previous contact with the peasant culture of his own land. And so on.

So, when faced with the analysis of a historical source, it is necessary to take references with tweezers and to understand the author's context: his/her place and time of origin, his/her language, his/her experience...

(To this must be added his/her fantasy. And that of his/her informants, very prone, at times, to provide false information or simple mockery to researchers ― who usually represented invasion and coloniality.)

All this reflection comes from a note by Swedish anthropologist and archaeologist Erland Nordenskiöld, who, in his work An Ethno-Geographical Analysis of the material culture of two Indian tribes in the Gran Chaco (1919), draws attention to the chronicles of the journey of Spanish conquistador Francisco de Orellana, during his "discovery" expedition along the Amazon River in 1549.

The text, Relación del nuevo descubrimiento del famoso río Grande que descubrió por muy gran ventura el capitán Francisco de Orellana ["Relation of the new discovery of the famous Great River that Captain Francisco de Orellana discovered by great chance"], was written by Fray Gaspar de Carvajal, a friar who took part in the voyage. The Relación... was published in full in 1894 by Chilean scholar José Toribio Medina, as part of his work Descubrimiento del Río de Las Amazonas ["Discovery of the River of the Amazons"]. Later, in 1934, it was extensively revised by H. C. Heaton, and republished in 1942.

In that diary (Carvajal, 1942), a curious three-stringed chordophone is mentioned, which the chronicler, following the Castilian tradition, calls "arrabel."

When we were halfway down the river, the Indians followed us by water, because the captain ordered us to cross to an island that was uninhabited, and until nightfall the Indians did not leave us; and so we arrived at the island more than ten hours after nightfall, where the captain ordered us not to jump ashore because the Indians might come upon us; and so we spent the night in our brigantines, and when morning came the Captain ordered us to walk with great order until we left this province of San Juan, which has more than one hundred and fifty leagues of coast, populated in the aforementioned manner. And another day, the twenty-fifth of June, we passed between some islands that we thought were uninhabited, but after we found ourselves in the midst of them, there were so many people that we saw on the said islands, that it weighed us down; and when they saw us, they came out to us on the river on two hundred pirogues, each one carrying twenty or thirty Indians, and of them forty, and of these there were many: they came very brightly dressed with various insignia and brought many trumpets and drums, and organs that they blow with their mouths, and arrabeles that they have with three strings; and they came with so much noise and shouting and with so much order, that we were frightened (p. 34, transl. by the author).

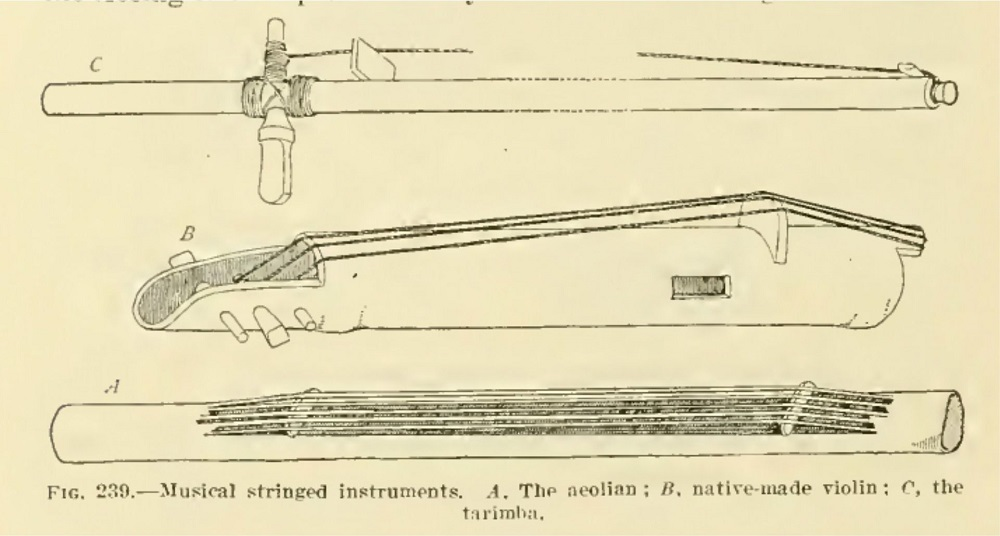

"Arrabel" is an old way of naming the rabel or rebec, a traditional fretted stringed instrument of European peasants, employed in Spain to this day in certain rural contexts.

That the chronicler chose that particular chordophone for his comparison —and not a plucked or bowed vihuela, or a lute— is revealing. For him, the "arrabel" was a crude and uncultured instrument: more a noise-producing artifact than a source of real music. (It is worth mentioning that this vision about the rabel was maintained in Spain for centuries.)

Carvajal's seems to be the only existing reference on stringed instruments in the shores of the Amazon River. But it is not the only one in that part of the continent. In the "eighth decade" of his Décadas de Orbe Novo, Italian chronicler (but in the service of the Spanish crown) Pedro Mártir de Anglería speaks of a similar instrument that he found in use in the region of Chiribichí (present-day Santa Fe, Sucre state, Venezuela), made with large seashells through which strings were crossed.

These are probably early borrowings and imitations of both Iberian and African instruments. Other examples of similar "arrabeles" are found among the Guyana people (Roth, 1924), among the Guarayo and the Caingang (Frič collection in Prague), and among the Nahuatl and the Huasteco peoples in Mexico (Basauri, 1928). But all of these, interesting in themselves, will be discussed on another occasion.

References

- Carvajal, P. Gaspar de. Descubrimiento del Río de las Amazonas. [Relación de Fr. Gaspar de Carvajal exfoliated from the work of José Toribio Medina, Seville edition, 1894]. Bogotá: Prensas de la Biblioteca Nacional, 1942, p. 34.

- Nordenskiöld, Erland. An Ethno-Geographical Analysis of the material culture of two Indian tribes in the Gran Chaco. [Comp. Ethn. Studies, 1]. Göteborg: Elanders Boktryckeri Aktiebolag, 1919, p. 168.

This post belongs to a compilation that has been published by El Zorro de Abajo Editora. That publication can be accessed through the section "Articles" at Instrumentarium.